Introduction to the Field of Cinema and Medicine

Intro

As a film major with the aspiration for a career in the medical field I constantly have been trying to relate cinema and medicine. Besides the obvious television and films about medicine and hospital like Grey’s Anatomy, Scrubs, and Contagion, cinema is used to make scientific advances, explanations, and even help to train medical professionals in a variety of skills. More than just instructional videos of surgical or other medical techniques, medical school curriculums have started to use cinema to analyze characters as positive or negative role models. There exists much debate on the clinical significance of using cinema for education, for which some of the more statistically significant results occur from training in recognition of patients with “overdose or alcohol withdrawal and also gave them an insight into potential severity” (Darbyshire 31). Cinema can help to develop an understanding of psychiatry, the relationships between people including the relationships between patients and their families and physicians. It can also help to develop better observational skills and visual literacy to establish a better picture of the ailments of a patient. This blog aims to describe different aspects of cinema through research and my own experience that can aid students or professionals in the medical field.

History

Over time the use of cinema in medicine has changed in its attempts to educate. In 1979 the role of cinema appeared to be primarily in psychiatric education. In 1983 studies surfaced using film clips to “facilitate tutorials around human sexuality” and to examine student attitudes about explicit content. These studies did not show much statistical significance of increase in any sort of skills. The 1990s were an important start to medical education through cinema with a large focus on DSM-III and psychology studies. In 1993 studies were performed on the effectiveness of teaching clinical pharmacology via the film Awakenings. In 1994 Alexander described the use of cinema to teach psychosocial aspects of medicine to family medicine residents. The articles discuss the use of clips from Taxi Driver to facilitate learning about the Mental State Examination. Articles between 1995-2000 discuss using cinema to facilitate discussions, supporting a specific point and maintaining audience attention were the main reasons for using cinema clips. Articles also touched on teaching pediatric nursing students about developmental standards and critical thinking skills, group counselling, and AIDS.

How to Choose a Good Film

Because the effects of studying cinema and fine arts in order to improve clinical skills are so controversial, studies have shown that certain element of a film are essential in order for it to be an effective learning tool. Josep-Eladi Baños in his research at Universitat Pompeu Fabra suggested that students watch films they are relatively unfamiliar with to “pique students’ curiosity and can increase motivation” (Baños 207). He also suggests that in order to understand some ethical conflicts, students need a certain “degree of intellectual maturity” (208). He uses the example of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as an example for discussing bioethics and ethical principles of biomedical research. While a first-year student might only see the wickedness of the monsters, it is important they have background knowledge on the ethical situations to look out for, to understand the wrongdoings and debate the ethical decisions made by the scientist. Another example he gives is the first scene of Wit, as a perfect example of how “how not to give bad news to patients” (208). The scene features a doctor telling his patient, a middle aged female professor, that she has a life-threatening cancer. The scene can provoke discussion in students by critiquing the physician’s delivery of poor and life-changing news. In the process of explaining he diminishes her intelligence and lacks any sense of empathy or chance for her to comprehend the news. In a sense their conversation becomes dehumanizing. A student who has not been in that scenario or has not yet learned about how to deliver such news might not even consider that the physician’s delivery was so poor.

(If you haven’t seen the movie Wit, it’s really good, but also extremely emotional and I cried.)

According to Baños other important things to consider when choosing a film are small and specific clips so that the learning objective is clear and narrowly focused. Analysis of films can also be beneficial for considering the hard science aspect of medicine. He gives the example of the film Coma and how although it is not quite scientifically accurate it can prompt a discussion about carbon monoxide intoxication and serve as a starting point for pointing out different affinities of gases to haemoglobin. It allows students to point out mistakes, and if they do not catch certain mistakes it can show which material or concepts they have not yet learned or do not fully understand (208). Lastly it is important to choose clips that can help to consider both the patient and physician perspective. From a humanistic point of view, and judging from the interaction shown in the first scene of Wit, much can be learned by considering the point of view of the patient through film, especially if the student has never been a patient or known close family to be a patient either.

Films that Baños recommends include: Doctor Arrowsmith, Ikiru, The Doctor, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, La Maladie de Sachs, Wit, The Constant Gardener or My Life Without Me.

Psychiatry

Psychiatry is a field of medicine for which students can greatly sharpen and improve their skills by studying cinema. Especially in the beginning phases of using cinema as an educational tool, many studies were done showing how people with different levels of intoxication or substance abuse might act. Also with influence from the DSM-III psychological and mental disorders became a prevalent topic within film study. Carla Gramaglia in her article “Cinema in the training of psychiatry residents: focus on helping relationships”, discusses studying film and medicine with relation to Carl Jung’s theory of archetypes. She explains,

an archetypical content can become conscious, and actualize its potential in the form of images, behaviors, patterns of interaction with the outside world. Images can therefore play the role of important mediators between conscious learning and unconscious archetypes. Moreover, our psyche speaks through images [22,24], and psyche can deal with the world or with itself and its functioning. Accordingly, images from a movie, such as those of a dream or a fantasy, can be read at two different levels, an extra-psychical (or objective) one and an intra- psychical one (Gramaglia 3).

The ability for us to consider symbols in film and relate them to a certain feeling or idea easily relates to observations in medicine. Certain signs or symptoms can be representative of an underlying issue or speak to a more wholesome picture of the situation. When watching a film, students in groups can identify with different characters and can discuss situations depicted in the movies from different perspectives. Gramaglia suggests role-playing of scenes with role inversion to “put feelings, emotions and thoughts into words” which can help with physician relationships as well as understanding patients and situations (2).

Another psychological aspect brought about by Jung is this concept of “shadows.” Gramaglia explains the relationship of shadows nicely by stating,

According to Jung, everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. Some of these dark, unconscious parts of personality can also show up in one’s job. For example, they can arise as the shadow side of power in the medical profession [36]. Power can lead physicians to swing between an exciting omnipotence (“I can do anything”) and an overwhelming sense of responsibility (“everything depends on me”); such conditions are both dangerous because they neglect the value of relationship and deny the importance of the patients’ role (2).

Certain films have the ability to focus on certain shadow sides that bring up valuable discussion on how to acknowledge and deal with those issues. In addition to certain shadows Jung’s concept of anima, “part of individuals enabling them to receive, to hold, to cry; to pay attention to details and shades, i.e. to achieve the discrimination of values depending on the feeling function (considering Jung’s model of the four functions); to go deep into meaning and pain; to promote and take care of life” also becomes an essential part of the learning experience of medicine through film. Understanding emotions is the first step to understanding empathy and allowing a prosperous physician and patient relationship. Understanding the patients’ emotions, the family’s emotions, and the physician’s own emotions, helps to greater understand each medical situation (2).

Some films recommended from this study: The Seventh Floor (Il Fischio al naso), The Closet, (Le Placard), M, The Remains of the Day

Strengthen The Humanist Perspective

Several studies and curriculum have attempted to express a humanistic approach to medical studies. One study at Xavier University School of Medicine focused on using movie screening and film activities to strengthen the learning of “communication skills, empathy, professionalism, and the greater understanding of the process of death and dying” (Shankar).

Movies in study: Wit, People Will Talk, The Doctor

An example of the curriculum for a well structured elective divides the class into four sections. The first is to view films with a deep understanding and analysis of the relationship between family and illness, the second, family and loss, the third, the family and caregiving, the fourth, family and substances, and the fifth, extended family and illness. All too easily people forget that the patient is not the only person who necessarily matters in creating a whole picture of the patient. The family is well affected by the patient and the patient is well affected by the family.

Recommended Films:

The family and illness-Films: Year 1: “Lorenzo’s Oil” and “The Straight Story” (Year 2: “A River Runs Through It” in place of “The Straight Story”

The family and loss-Films: Year 1: “Ordinary People” and “Barbarian Invasions” (Year 2: “The Trip to Bountiful” in place of “Barbarian Invasions”)

The family and caregiving- Films: “Marvin’s Room” and “Iris”

The family and substances: “When a Man Loves a Woman” and “The Days of Wine and Roses”

Extended family and illness: Films: Year 1: “Flawless” and “My House in Umbria” (Year 2: “Beaches” and “Barbarian Invasions”)

An important testimonial that explains a very important point: “I think I’ve become more aware of the different ways in which families deal with illness. There is a lot of diversity in this respect, and it was valuable for me to be in a group situation and to hear others’ perspective on this subject. In caring for patients, it is so easy to assume that the definition of what makes a family is similar for all people. It is also easy to think that all patients may confront illness and death and dying in the same way. Through a variety of films and the group discussion, this class helped me to learn different ways in which people and families cope with the emotional and physical burden of illness. It also helped me to appreciate the way in which movies can be a useful educational tool” (Weber).

Observational Skills and Visual Literacy

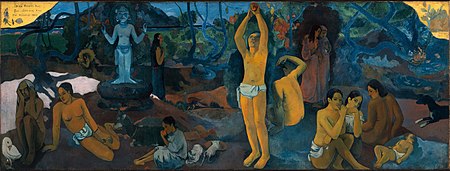

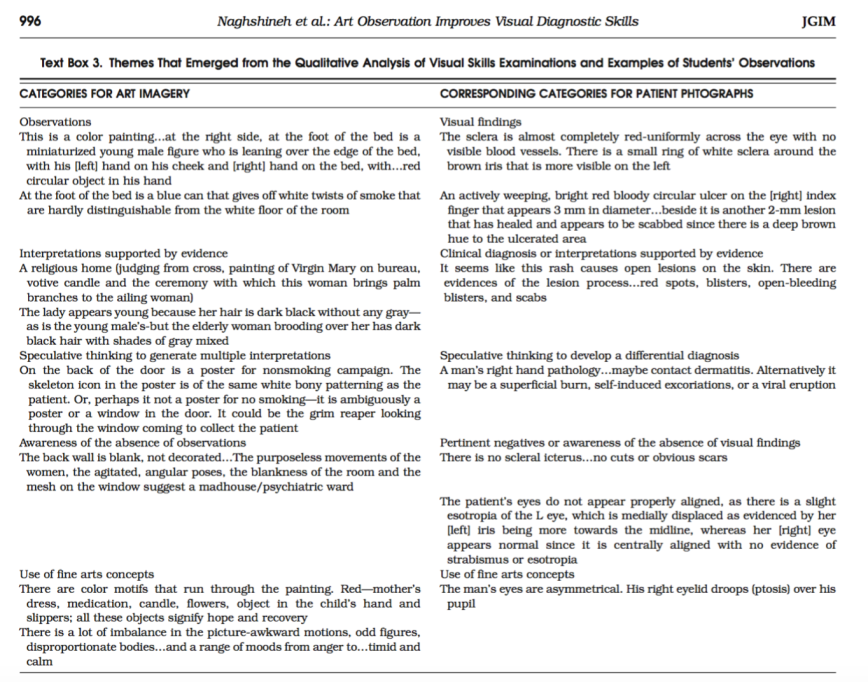

Recently there has been a decline in the observational skills of medical students and professionals as well as decline in the use of fundamental bedside procedures such as inspection as opposed to lab tests and radiological studies (Naghshineh). Studies suggest that there are “opportunities to improve patient care with implementation of better physical examination teach methods” (Naghshineh). Several studies exists of curriculum using visual art such as examining paintings, cinema, or photography in order to teach “visual literacy.” Naghshineh describes visual literacy as “the ability to find meaning in imagery, which in medical parlance translates into the ability to reason physiology and pathophysiology from visual cues.”

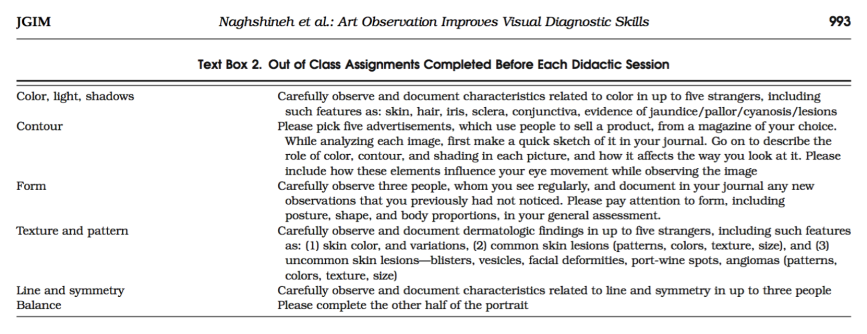

Certain visual arts classes explored relating artistic concepts to specific components of a physical examination. Some examples of clinical findings discussed during these ranged from, “dermatology (palor, jaundice, erythema, vesicles vs. papules, grouped lesions) to pulmonology (stomach-breathing, use of accessory breathing muscles, pursed lips) and neurology (cranial nerve III, IV, VI, and VII palsies, and gait)” (Naghshineh). Below is a sample assignment, forcing students to use these visual arts observational skills to apply them to observations about a person or patient.

Examples of paintings include:

This photo is Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? By Paul Gauguin

The aim of this photo is to consider the artistic elements of color, light, and shadows. Medically the aim is to help consider “color and luminance” which is important for determining and making observations about the colors or a person’s skin or eyes that might indicate illness. For example yellow tinted eyes as an example of jaundice, bruised skin as an indication of anemia, or pale or blue lips as a sign of hypoxia.

This photo is The Summer Night’s Dream by Edward Munch. It is used in the curriculum to discuss contour, and specifically in the medical aspect, contour in thoracic radiological image.

This photo is The Summer Night’s Dream by Edward Munch. It is used in the curriculum to discuss contour, and specifically in the medical aspect, contour in thoracic radiological image.

This photo is The Execution of Emperor Maximillian by Edward Manet. The goal of this picture is to examine form, or in medical terms “Linking Form to Function in Pulmonary Pathophysiology. From observing small details about form such as the way the people looking over the wall have their hands on their heads or even the jugular distention of the man being shot expresses symptoms a patient could be having. For example, noticing the posture of a person sitting or standing, bent over, with their elbows or hands on their knees in called tripod position and is frequently a sign of respiratory or cardiac distress .

.

Number 10 by Jackson Pollack considers the artistic aspects of texture and patter. while medically to consider is “texture and pattern recognition in dermatologic diagnosis.” The ability to describe the colors and textures involved might help somebody to diagnose the specific mark or deformity on a person’s skin.

Another important skill in addition to making these artistic and medical observations is the ability to articulate them thoroughly and clearly. The ability to describe specific details about art translates to the ability to describe specific details about a patient such that a clear and descriptive picture can be created about the patient’s situation. Below is a list of examples of good descriptions of observations of art and of patient photographs.

Personal Experience and Skills

I can definitely see how looking at art and being a film major can realistically increase observational skills, visual literacy, and help to consider a humanistic and psychical approach in the medical field. Personally as an EMT, I have experienced how helpful it is to have good observational skills that can be translated to words. During a trauma assessment an EMT must look at the patient’s body from head to toe and call out every single observation or malady visible for another EMT to write down. Since we do not perform scans or blood tests on sight we must rely on visual and auditory cues such as color, texture, and sound quality, to understand what is going on. One must then extrapolate and create a larger image of what might be going on with the patient, and the more detailed and accurate the written report it, the better picture the doctor gets upon arrival in the hospital to give the best treatment.

Mostly I’ve considered the importance of what skills I’ve learned as a film major that translate to how I would be a good physician or medical student. I’ve considered how constant studies of cinematic techniques such as lighting, depth of field, film speed, frame rate, angles, take duration etc. influence the work as a whole and make up all of the parts of a scene. The ability to make these observations and be able to describe all of these elements would help with my observational skills and visual literacy. Additionally, in classes like History of World Cinema and Film Theory, I’ve greatly developed my critical thinking skills. I’ve learned to ask why and how to almost every concept in film applicable, and I think that will help me in my curiosity toward medicine and ability to consider patients’ cases in the future. Being a film major has helped with my leadership skills in all of my production classes. The ability to direct actors while corralling the cinematographer, gaffer, sound producer, the rest of your crew and plenty of expensive equipment takes a remarkable amount of organization, teamwork, and leadership. Additionally production classes have taught me how to think quickly and calmly on my feet. Almost inevitably a multitude of misfortunes and unexpected issues arise during a film shoot for which you must figure out a way to carry on. Perhaps a your actor is sick, theres a rainstorm, or the tripod breaks, you have to figure out how to keep the show rolling, and you usually, even if not gracefully, figure it out. Think about how what you’ve learned in cinema studies overlaps with your interests. Guaranteed it probably overlaps somehow in a helpful and engaging way.

Works Cited

Baños, Josep-Eladi, and Fèlix Bosch. “Using Feature Films as a Teaching Tool in Medical Schools.” Educación Mécdica, vol. 16, no. 4, 2015, pp. 206–211.

Darbyshire, Daniel, and Paul Baker. “A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis of Cinema in Medical Education.” Medical Humanities, vol. 38, no. 1, 2012

Naghshineh, Sheila, et al. “Formal Art Observation Training Improves Medical Studentsâ Visual Diagnostic Skills.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 23, no. 7, 2008

Shankar, Pathiyil Ravi. “Using Movies to Strengthen Learning of the Humanistic Aspects of Medicine.” Journal Of Clinical And Diagnostic Research, 2016

Weber, Catherine M. “Movies and Medicine: An Elective Using Film to Reflect on the Patient, Family, and Illness.” Literature and the Arts in Medical Education, vol. 39, no. 5, 2006.

I Just Wanna Play My Music: The Role of Music in Film

Introduction

If you have ever watched a film muted, you can’t help but notice how the experience changes. The link between film and sound, particularly music, was established early in the history of the medium, and the relationship has become very closely tied. Even during the silent cinema period scores were added and/or played live to accompany the moving images. We’ll briefly discuss the move towards this inclusion of sound in cinema and how it became such a vital component of filmmaking.

It’s hard to pinpoint any specific role music plays in film because it can serve such a wide variety of functions. In general, music can serve several purposes that are either important on the emotional side of the movie or help/enhance the storytelling. Music can help the images on screen seem more true to life, emphasize emotions, alter perceptions of time, and can change the audience’s perspective of a scene altogether simply by a change of chord. While it is doing all of this, “film music encourages our absorption into the film by distracting us from its technological basis—its constitution as a series of two-dimensional, larger-than-life, sometimes black-and-white, and sometimes silent, images” (Kalinak, 2010). Of course, film music doesn’t do all of these things all of the time. But music is so useful to film because it has the potential to do so much simultaneously. As filmmakers, it’s important to understand the role music can, and most likely will, play in your own films and how you can start to develop yet another essential tool in your filmmaking toolbox.

A Brief History of the Evolution of Film Music

Why did music come to accompany moving images at all?

Film exerted a gravitational pull toward music from the very beginning; though the standard explanation for the combination of image and music is functional: music compensated for the lack of sound in silent film, and it covered the noise produced both by the projector and by audiences unschooled in cinema etiquette (Kalinak, 2010). Music was readily available in the early homes of cinema, the cafes, vaudeville theaters, music halls, carnivals, and traveling exhibitions where musicians would play for the moving images on the program as they would for live performances. But noisy projectors and audiences were soon quieted, motion pictures moved into their own screening spaces, and it wasn’t long before synchronized sound became the norm. Yet musical accompaniment persisted in film long after its initial utility had faded.

The trajectory that the relationship between film and music has taken, I believe is in part due to the role that music can play as a means of storytelling. Though music, the use of sound in general, had been cautioned against by many theorist and filmmakers of the silent period, music much like sound, when done appropriately, have the ability to both unlock and enhance new potentialities of the medium. By this I mean that certain qualities of film e.g. subjective alignment with characters, interpretation of tone, emotion, and the passage of time are all things that we have learned can be established and/or emphasized through the incorporation of sound, and specifically for this post music.

(Here I’ll add more based on today’s comments.)

Some Common Functions of Music in Film

Diegetic Music

As a function of music in film, diegetic music is as you might guess from the name, music that can be heard both by the viewing audience and by the characters in the film. Examples of this sort of music include car radios, music heard from a CD player, or even a live band in the film. The scene below is a quick excerpt from Her (2013) in which the two main characters are improvising a song:

Diegetic music can have a lot of positive impacts on a scene. It can behave almost like dialogue would at times. We see this often in teen movies where for example one character wrote a song and performs it in front of their person of interest. It can have an expositional purpose: if we think of the amount of scenes in movies that feature a character or two listening to a song they really like that helps show us rather than tell us something about that character as a person. In any case the music choices being made are serving to help propel and/or enhance the narrative arc. That is one of the more promising potentialities of sound design, and film scoring in particular, that it doesn’t always serve such an internally motivated purpose, but when it does it becomes so integral to the scene that something would truly be lost in its absence. Below are a few scenes that incorporate diegetic sound in different ways and for different ends. I think they both do so successfully, so I include them here as an example of some of the ways this type of sound can work.

Setting

Music as a function of setting can do a few key things. Perhaps the most obvious of these being helping to establish the film’s world. If, for example, I have set my film in Italy the choices I make musically can have a great impact on both the believability and the overall feel of the film. Particularly in considering non-diegetic music choices, if I’m telling a story about a small village in traditional Italy, I should have already done some research on what instruments and what particular styles of play are characteristic there. Musical choices can be the difference between a well-crafted and well-received score and something that just seems like an unmotivated attempt at adding another dimension to a scene.

Emotional Enhancement

Another very strong function. Music can serve the movie by getting into the emotions of the characters. A face with a neutral expression can be pushed into “feeling” many different things just by what kind of music is used. In the same way it works of course very well to evoke certain emotions with the audience. This sort of effect works both to emphasize pre-existing emotion in the film whether that be visual, spoken, etc. and to add a new layer of emotion in support of and/or in contrast to the emotive qualities of the image. In both cases, the music becomes central to the work itself. Its inclusion becomes integral to the weaving of the story, to the portrayal of the affect; whatever specific function it plays, the image is enhanced by its presence.

Here is a quick example of a scene from La La Land (2016) that I think does a good job of using the score, as diegetic sound, to portray and emphasize the emotional weight of the scene. A scene which might I add was pretty sad even on mute but brought me to tears the first time I watched the film.

And another short clip from a short film I co-directed that I think also demonstrates this:

I think of the Kuleshov effect that colors some of the theory behind particular types of editing. The way in which we could have the same image impress different emotions on an audience simply through changing the images surrounding it. Likewise, I believe that the choice of music that accompanies an image can affect the way in which the audience perceives the emotional state of the character. I’ve put together a brief video that is quite on the nose but helps as a base demonstration of this “musical” Kuleshov effect:

Montage

Music helps very well to glue scenes together. Rather harsh scene changes can be softened by adding music over the scene change. One of the extremes of these forms are montages which work beautiful with music. Even though we might have a lot of jumps in time/places or even periods, when the montage is covered under one score cue it will at the same time be glued together and understood as a whole. It can also work to express the passage of time itself. Where we sometimes have sequences of images that are more so an expression of changes through time than a connection of differing narrative arcs, we might also see music being used to help convey both the emotive undertones of the images and the concrete acknowledgement of a passage of (sometimes indistinctly prolonged) time.

In the following scene from The Twilight Saga: New Moon (2009), we see both usages of the music/montage pairing. We have the beginning scene that establishes that months have passed even though nothing in the space (not even her outfit) changes. Then we have a montage of images that establish the life of her and the people close to her (or that were close to her) throughout another undefined length of time. All of this was partially brought together by the soundtrack that they chose to accompany the image. This without mentioning the song itself which given the wider context of the film, and the series, also serves to emphasize some of the character psychology that we come to recognize as distinctly Bella.

Build Suspense

Music can also be used in a film to convey anticipation of a subsequent action. Sort of a self-explanatory function, here the music quite literally builds suspense that suggests the action to follow. It could change from light and happy to more dark and sinister or go from a soft soothing sound quickly to a sharper more forceful sound. Either way, these sudden changes create tension since the audience is unaware of what is to follow.

We see this technique used a lot in horror or thriller movies. In conjunction with jump cuts and other visual cues, the added music changes the audience’s mood entirely and provokes strong emotions from them, or at least in a horror movie it lets us know when we should cover our eyes! We just need to keep in mind that with this particular function the music and the image should be fairly related to each other to properly achieve the effect. In the scene below from Monster’s Inc. (2001), it’s not necessarily a horror or thriller film, but you can certainly see how the score is molding the suspense building of the scene up unto the big “scare” moment.

Conclusion

This is far from a comprehensive list of the ways in which music can impact your visual storytelling, but these are some of the key functions it can serve. This essay was not to be prescriptive in telling you which ways to use music and which ways not to. Rather my goal here was to give you some things to consider before you make the decision to include music into your own work. Bad sound design is one of the pitfalls that student films face often and an unmotivated inclusion of score or soundtrack music does nothing but add to that negativity. I, for one, am a proponent of the usage of music though I seldom do so in my own work. I think that much like we spend a substantial amount of time learning about image composition, parallel editing, and what have you, so too should we spend time learning about how we can use music to tell a compelling story and for that matter why we would use music in the first place. It’s my hope that this post can be a starting point for some of you that are hoping to make your own films and may not be sure how you can incorporate music artistically and purposefully.

References

Kalinak, K. M. (2010). Film music: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

No cited but another great book for further reading:

Aesthetics of Film Music by Zofia Lissa

hello, this is my draft/notes/what i have so far. it really just needs to be consolidated and finished and with media elements added

Launching your Creative Career

If you’re seriously considering pursuing your creative passions, chances are you’ve already overcome a lot of adversity. You’ve answered “what are you going to do with that major?” a million times, you’ve created work that you can show as your own, and you’ve already made arrangements on your parents couch. What’s next? There are a lot of options to explore: you can try to work for an established company, or you can be your own boss. With the growing “gig economy”, more and more people are branching out on their own. This guide will help you learn more about ins and outs of freelance work.

Starting Off

Align your interests

Taking the plunge into freelance is a huge endeavor, so you have to be sure you’re equipped to do venture out and do what you love. The first step to doing that is figuring out what you have to offer. Are you a master cinematographer? Do you love writing? Are Premiere and Avid shortcuts second nature to you? Determining your skill set will help you figure out what your best bet as a freelancer is. You can take this quiz to help you figure it out: What Freelance Career Is Right For You?

After you know what you want to do, figure out who you want to work with. As a cinematographer, are you interested in capturing weddings or do you want to go into film? What types of things do you want to write? As you answer these types of questions for yourself, you can better determine the types of people you should be marketing yourself to.

Develop your Brand

As cheesy as it sounds, you are a brand, and people are more likely to work with a person they trust then someone who they don’t know about. That just makes human sense. That’s why developing your brand is one of the most important things you can do as a freelancer. What does that mean? Your brand refers to how you present yourself to others and how you are perceived. It doesn’t have to be artificial. Your brand includes qualities like your personality and what services you have to offer. It doesn’t have to mean stuffy and corporate, after all isn’t that part of why you’re doing freelance? Some steps to developing a brand take a long time, but there are some things you can do now or in the next week to help shape your brand perception.

Things you can do now:

- Check out your social media. Yeah, we’ve all heard that potential employers are looking at your social media, but more importantly for you, so are future customers. Do they know what you have to offer?

- Tell you friends and family. The people you already know are some of your biggest assets. Let them be your advocates.

Things that will take a little longer:

- Develop a website if you don’t already have one. In this day and age, your digital footprint is your biggest mark on the world. Make it a size 18. Check out this great example.

- Make business cards. Believe it or not, people still use them

Surviving

Network

Networking is an unnecessarily scary word for a pretty simple task: talk to people. Get your name out there. Find people you’d like to work with or bounce ideas off of. Just because you’re interested in doing freelance work doesn’t mean you’re doing everything alone. Through networking you can find people to collaborate with and potentially people who will hire you. There are so many places to connect with people, most notably LinkedIn. However, in your chosen field there are established communities that are ready to be explored. You can search for a local union or interest group to find like-minded individuals. If there’s not one in your community, maybe you can start your own. If networking still sounds less than ideal, check out this podcast on the Networking:

Find Work

Finding work as a freelancer depends a lot on people being able to find you. This is one reason why creating connections with people is so important. Many freelancers point to word of mouth as one of their most successful means of finding work. However, there are other options to explore. Sometimes, taking temporary jobs can help lead to more consistent work. There are also hundreds of websites out there that aim to connect people to employers. On the more creative side, Upwork, The Shelf, and LinkedIn Profinder all work as freelance job boards. For a long list of more, check out this Forbes article.

Thriving

Manage your Money

As a freelancer, you’ll have to be a Jack of all trades while still being a Master of One. This means you’ll be in charge of your own schedule, managing your clients, and often the most daunting, managing your money. With freelance, managing your money is more than just budgeting to make sure you can eat meals and pay bills. It’s prepping for the variable income between months where you receive a lot of work to months where you receive less work. It’s also making sure you pay taxes and save for the future. Whereas in an established company, these things are often handled through Human Resources and Accounting, in freelance HR translates to YOU.

One of the things people most ignore, especially those just starting their careers, is saving for retirement. This is especially forgotten amongst freelancers, but it is just as important. Knowing the difference between a Traditional IRA and a Roth IRA will make a world of difference with your money life.

Like I mentioned, money is perhaps the most terrifying part of freelance, and since money makes the world go around, that’s not to be taken lightly. However, there are plenty of resources to help you learn more about your money. To start off, check out the Payoff’s Freelance episode.

Keep Learning

Creative fields are constantly changing and morphing. Because of that, it’s important to stay informed on what’s happening in your industry. With the internet at your fingertips, there are so many ways to stay knowledgeable. Here are some resources I’ve found across fields that have been useful.

Podcasts

The Payoff by Mic – teaches you ins and outs of money

The Wandering DP – tips and tricks for those interested in cinematography. Also includes website with tutorials

Creative Communities

Creative Mornings-a monthly meeting of creative hosted in cities nationwide. Each month has a certain theme and includes talks from a creative professional on that month’s theme.

Stareable-a web series community where people share ideas and advice

With these tools, and the world as your oyster, you’ll be a freelance guru in no time. Best of luck!

Sources:

https://www.creativeboom.com/tips/how-to-survive-your-first-year-as-a-freelancer/

https://www.mepragency.com Branding Workshop

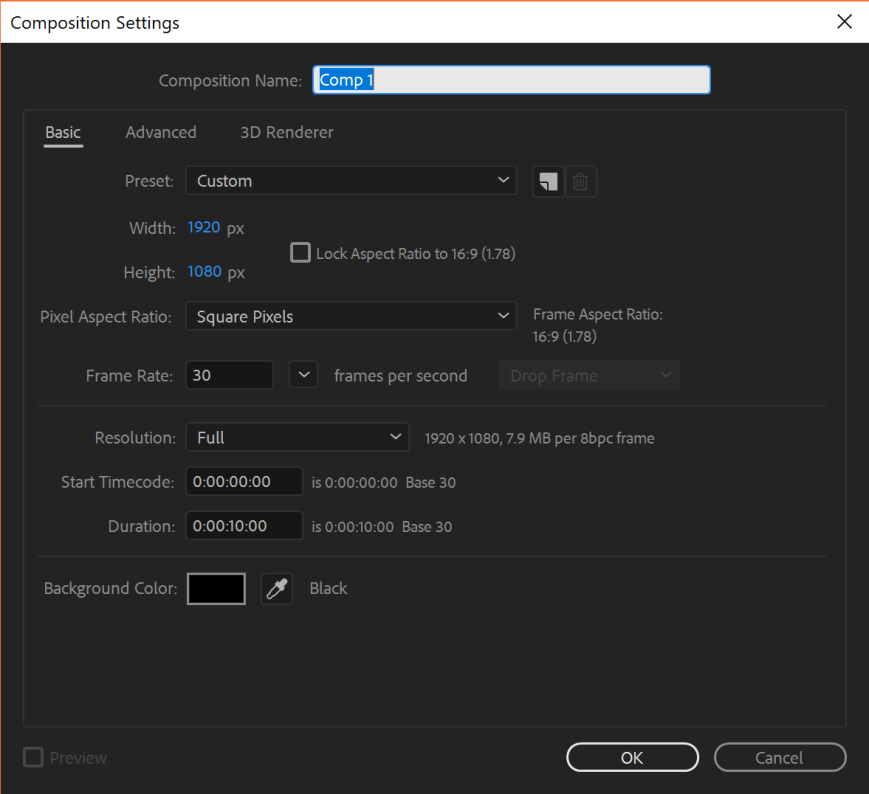

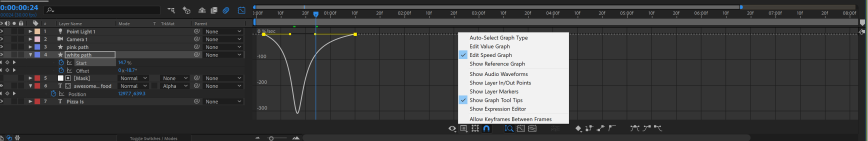

How to make a cool intro with After Effects

Tutorial:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CKDWSMVThe7ya69DtYeeT9u-DqsykyvN/view?usp=sharing

Supplemental information

-

- Compositions: You must make a composition before anything else

- Compositions: You must make a composition before anything else

- Layers: Layers stack! So if you have multiple layers, and you don’t see one, it’s probably hidden behind something else. Layers can be created by going to Layer-> New.

- Key frames: They define the starting and endpoints of an animation. You can add key frames by clicking the stopwatch button next to certain properties (position, scale, rotation, etc.) Some key frames may be automatically created if you move your object. Key frames allow you to animate your composition and change properties over time.

- Key frames specific to this animation: Start your text layer a few lines lower than where you want the text to show. Add a position keyframe. Move your cursor (or click shift+pg down), and add another key frame. This will be the amount of time your word shows up on the screen before shifting. Then, move your cursor down (I moved mine 5 frames down) and move your text layer to the next word (this will automatically create a new key frame). This will be the amount of time it takes for your words to shift, so choose accordingly. Do this for every word, but make the transition times shorter toward the end in order to have that spinning effect. You can skip words toward the end, so you don’t have to stop each time.

- Easy Ease: You can easy ease your key frames by right clicking them, going to key frame assistant, and clicking on easy ease. This allows the animation to start off slowly, ramp up, and slowly die off. Helpful for making your animations look smoother and less stiff.

- Trim paths: You can add these to shapes, and it will animate the path of the shape. You can change the speed, direction, and position of the path. By changing the offset property, you can make your path start later or earlier than the default path. Under shape layers, you can click add->trim path.

- Timing: If your timing doesn’t look the way you want it to, there are a few things you can do.

- You can go to the graph icon in the top right corner of your controls. Here you will be able to edit the speed of your key frames. If you don’t see a speed graph, click the icon next to the little eye and that will allow you to change which type of graph you are seeing. Be sure to click on your graph lines so that the yellow dots are visible. These yellow dots will allow you to change the speed without having to move key frames. You can move them inward to make it faster, or outward to make them slower.

- You can also move the key frames in your time line inward/outward. This will change the amount of time it takes for your animation to finish (unlike the graph option). You can highlight multiple key frames at a time and move them. If you want to move them proportionally, you can highlight them, and alt+click the last frame you’ve highlighted.

- Easy ease will also help!

- You can go to the graph icon in the top right corner of your controls. Here you will be able to edit the speed of your key frames. If you don’t see a speed graph, click the icon next to the little eye and that will allow you to change which type of graph you are seeing. Be sure to click on your graph lines so that the yellow dots are visible. These yellow dots will allow you to change the speed without having to move key frames. You can move them inward to make it faster, or outward to make them slower.

- Windows: If there are windows you don’t see, like align, character, and effects windows, you can find them by going to the Windows tab and clicking whichever one you’re looking for.

- How to add a mask: You can add a mask by creating a new solid. From there you can create your mask by clicking the rectangle icon at the top (or whatever shape) and creating the shape on your composition. Make sure your solid layer is highlighted when you make the shape. The mask will be helpful if you want to hide things (like the shifting letters I made).

- Rulers: Rules can be found by going to the View tab -> Show rulers. You can drag the rulers down from the x and y axes. These can help you align your composition

- TrkMat and controls: TrkMat allows you to make some layers “Alpha Matte, ” which determines transparency of pixels when two layers are overlaid on top of each other. If you can’t find this option, go to the bottom of your control area and click “Toggle Switches/Modes.” In your control area you can also add motion blur to your layers and make them 3D. If you use motion blur, make sure to click the enable button next to the graph button.

- 3D. You can make some layers 3D in the control area. This allows you to use things such as cameras and lights. If you add cameras and lights, they will only affect layers that have the 3D mode on. Lights allow your 3D layers to have depth, since they create shadows. If your layer is 3D, you can change the extrusion depth under geometry options under that specific layer. This will make your object appear thicker.

- Shortcuts:

- Pg dn: moves cursor to next frame

- U : on selected layers, clicking U will drop down only the properties that have keyframes

- How to export: when you’ve finished, you can go to Composition-> add to render queue. From there, you can change may settings like resolution and quality. I usually only change the settings under Lossless. If you want your background to be transparent, click Lossless, and under Channels, switch it from RGB to RGB plus alpha. Don’t forget to output the file to the desired folder. Click render :b

How to Write a Joke: 10 Ways to Make Your Screenplay Funnier

1. Find your own comedic persona

They say it takes a comedic writer ten years to develop their comedy persona. But with the head start I’ll give you here, you can nail it in like eight. So first let’s talk about what a comedy persona is. Then we’ll talk about how to identify yours—and what to do once you have.

What’s a persona?

First, here’s what it’s not. For your purposes, it’s not a “character.” Some writers deliberately develop fictional identities or caricatures that may or may not align with their off-script personalities. But what we want to get at here, first, is authenticity.

So a persona is not a character, it’s your character. It comes from your personality, your take, your attitude, your bearing, your point of view, your general lens on life.

Your persona is what makes your jokes your jokes. Anyone can write a joke about parents or dogs vs. cats or homework or taxes or gentrification or doughnuts. But only you can write a joke about your unique take on those topics.

Example: Take this joke from Lauren Lapkus. You can get a sense of her persona without seeing or hearing her—just by reading these 18 words:

“I believe that each person can make a difference. But it’s so slight that there’s basically no point.”

From this joke, we can surmise that her persona is perhaps cynical, maybe glass-half-empty—at any rate, not the Pollyanna peppiest.

Of course, neither Lauren nor you are just one thing all the time. In real life, you shift somewhat according to context and mood. Your script—and your persona in general—will not be all one-note either. Not every joke will be angry, not every joke will be bubbly. You can have one pretty constant persona in one piece, but lots of different attitudes and emotions can come from it.

Where do you find your persona?

To find your authentic comedy persona, we are going to start with your original factory settings. Your persona is who you already are. At least that’s where it starts. This is NOT AS BORING AS IT SOUNDS. In fact, it is GREAT NEWS. It means half the work is already done for you!

So your comedic persona is a slightly exaggerated version of you. Here’s the equation:

PERSONA = REAL YOU x 1.3

And why is it great news? Well, let’s say you’re reading this thinking: “But I don’t haaaave a persona! I’m boring.” Guess what? Are you ready? THAT’S YOUR PERSONA.

So let’s see. Are you cynical? Sarcastic? Super-trusting? Lazy? Nervous about everything? ANGRY ABOUT EVERYTHING? Shy? Puppy-dog positive? Generally just confused? Tightly wound? Awkward? A rebel? The eternal teacher’s pet? An insider? An outsider?

The persona of the writer is what will give your script its flavor. For example, here are a few writers with their personas that you may already unconsciously recognize in their screenwriting…

Adam Sandler = goofball

Judd Apatow = immature loser

Tina Fey = witty, sarcastic

Abbi Jacobson & Ilana Glazer = optimistic stoners

Donald Glover = lovable nerd

Find one to two words that fit your comedy persona and explore those parts of your personality.

2. Find your SCRIPT’S persona

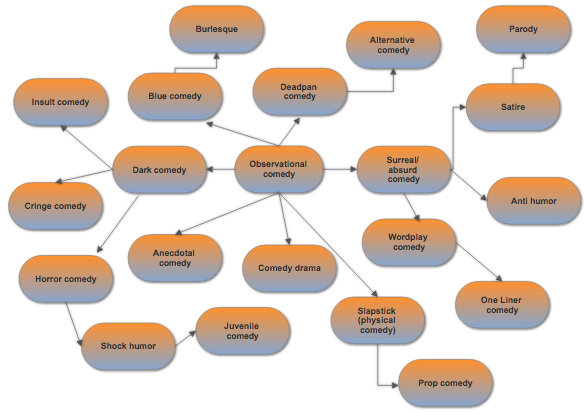

Maybe you’re writing a movie. Or maybe you’re writing a television pilot. Whatever you’re writing, you probably have some sense of the genre that it will fall under. Comedy is a huge umbrella term that could describe all sorts of styles and archetypes. Is your piece a rom-com? Is it more absurdist? Is it dark humor? Is it deadpan? Is it slapstick?

Knowing your script’s persona is a HUGE step towards writing a great screenplay because it means that you now have a ton of movies to watch! Watching movies that share aspects of your script’s persona can help you discover tropes and storytelling devices that are PROVEN to work.

Of course, just like your own comedic persona, your script’s persona doesn’t have to be just one track. But bear in mind that a sudden “slip on a banana peel” might feel a little out of place in a movie about cheeky orphans. It’s good to keep everything in a general tone with a few unexpected moments not too far from your base genre.

To help you out, I’ve made this Comedy Genre Web™ that will help you figure out if a joke will fit appropriately within your script’s persona. Though I don’t have the space to explain every flavor in this blog post, I will point out that observational comedy- which is comedy about the general mundane things of life- acts as the centerpiece from which all of these genres branch off. I’d recommend not hopping more than 3 bubbles away from your base genre to avoid throwing your audience off too much.

3. Understand different types of jokes

First step: learn and practice the 6 essential types of jokes.

-

Setup…PUNCH

This is the mother of all joke structures. Here’s how it works: set people up to expect one thing, but then POW! Surprise! You went in a different and unexpected direction. Comedy is all about the unexpected. The baby saying “goo-goo ga-ga” isn’t what makes us laugh. It’s the baby saying “Hey, pass me the cigar!” that gets a chuckle.

Can you guess the classic example of setup/punch?

Here’s a hint: it’s perfect because it’s so short—only four words!

It’s an oldie.

Here you go: “Take my wife. Please.”

See how Henny Youngman did that?

“Take my wife” makes you think he’s saying: “Take, for example, my wife. I am about to tell an amusing story about how much I love and respect her.”

“…Please.” = Boom! “Take her away from me! She’s an annoying nag!”

So that’s it. Setup, punch. Bait, and switch. You make the audience think you mean one thing, then you PIVOT. That’s the fundamental structure underlying almost every joke in the world. Sometimes the setup is just implied, sometimes the punchline is just silence. Sometimes the setup is a line of dialogue and the punchline is an action. Start listening for it when you watch comedic films and shows, and you’ll see it almost everywhere. In fact, if I’ve done my job right, you won’t be able to UN-see this structure in every joke, and comedy will no longer be fun for you. Sorry!

2. Triple + List

These are basically the extended versions of setup-punch.

Triple

The comedy principle at work here is the “rule of three.” Basically, it’s setup, setup, PUNCH. You give the setup more time to…set up, before the punch. You bait them longer before the switch.

The #3 doesn’t have to be a knock-your-socks-off shocker; it just has to be different from #s 1 and 2.

This structure can follow many patterns, such as:

- Normal, normal, JUST KIND OF SILLY AND RANDOM.

- Normal, normal, WTF? A huge pivot that changes everything. Here’s one from Jon Stewart: “I celebrated Thanksgiving in an old-fashioned way. I invited everyone in my neighborhood to my house, we had an enormous feast, and then I killed them and took their land.”

List

The most famous, least safe for work/school example is George Carlin’s “7 words you can’t say on TV,” which he refined and supersized over the years. Google it. I’ll wait.

Here is a list of the general properties of lists:

- Lists have more than three elements (otherwise they’re triples!)

- Lists work well when the elements contrast all over the place.

- Lists can be funny by virtue of being extremely, even uncomfortably long.

- Callbacks work great in lists. (We’ll talk more about them soon.) You could repeat a word or reference from earlier in your set, or even earlier in your list, if it’s a long one).

3. Comparison

A COMPARISON joke often takes the form of a simile or metaphor. Or it can be more indirect. This is a SUPER common joke style in stand up sets and works well in dialogue if one of your character’s is bold enough to make it.

Simile

Refresher from English class: a simile is a comparison using “like” or “as.”

“You look like an avocado had sex with an older, more disgusting avocado.” — Deadpool, 2016

[to his father’s ashes] “Dad, you were like a father to me.” – Due Date, 2010

That last one’s a great example of a Setup/Punch mixed with a simile!

Metaphor

You could describe a metaphor as like a simile, except you don’t say “like” or “as;” you just say the thing is the thing.

As in: (About people who keep bugging her to do CrossFit:) “OK, if I do CrossFit, can we at least agree that the people who do CrossFit are the Scientologists of the workout world?” —Brooke Van Poppelen

4. Callback

A callback is a reference to or out-and-out repeat of an earlier joke, line, standout word, or action. Callbacks themselves don’t even have to be funny or organically relevant. Audiences love them because they feel in on things. So they’re basically a totally free joke for you. They’re also great to close with.

5. Tag

A tag is a bonus joke tagged onto the end of what is already a complete joke. The joke is complete without it. But the tag gets you a free extra laugh.

Here’s the great part. A tag actually doesn’t have to be a fully formed joke. You can actually just:

- Repeat a word or underscore an emotion from your joke.

- Add detail that builds the joke and stretches out the laugh.

Take this famous scene from When Harry Met Sally… for example…

SETUP: Billy Crystal’s character bets Meg Ryan that he’s able to tell the difference between fake orgasms and real orgasms.

PUNCHLINE: Meg Ryan proceeds to have a very convincing and loud fake orgasm in the restaurant they’re in.

TAG: Other woman at the restaurant puts in the nail in the joke coffin by saying, “I’ll have what she’s having.”

The laugh was already there as Meg Ryan writhes and shrieks in the restaurant, but this last line really cements the absurdity of the situation.

4. Put your funny ideas in the right spot

Half the battle of writing a good comedy script is not knowing WHAT jokes to write, but WHERE to put them. For example, if you have a hilarious idea about a dog performing heart surgery on his owner, it’s better to actually SHOW the scene of Dr. Dog than just having your human character recount the story later.

Maybe your idea of an introspective Buddhist monk who’s experient inner existential crises may be better suited as a book than as a web series… Actually, now that I think about it, that sounds like it might be pretty funny. But it’s good to keep in mind which jokes work best as a short film, as a sketch, in a sitcom, or even in a stand up set.

Dialogue vs. Actions

In screenwriting, there are two venues for storytelling: character dialogue and action sequences. When most people think of a funny movie, they think of quotable lines spoken by characters. But a story with just a bunch of witty banter and talking back and forth is going to get old after a while. Unless you’re Woody Allen. And even then, sometimes it can feel a little hack. Or pedophilic.

Most movies will have a good mix of both funny dialogue and funny scenarios that set up each other and vice versa. Go through your script and see where the majority of the comedy is coming from. I like to write a star where I expect a laugh. Then I go through and count the stars that are coming from dialogue and the stars that are coming on action lines, to ensure that I’m not leaning too far in one direction.

5. Keep your characters real

Not every character can be a Sherlock Holmes or an Iron Man, constantly coming up with witty comebacks and super smart quips. Thanks Robert Downey, Jr., for really cornering the market there. Sure, the funny sidekick is a reliable trope that has stood the test of time but trust me, you don’t want to write just funny characters. Your characters will be even more funny if they have other human aspects, too!

Think about your characters’ backgrounds. What has happened to them in their lives that makes them act/speak the way that they do? This might seem obvious, but actually listing out your character’s quirks, aspirations, desires, history, and perspective will help you write characters that don’t just sound like your own voice over and over again.

As the old saying goes, comedy + tragedy = time. Think about how your character would respond to their worst nightmare coming true. This might tell you something about their more basic human nature and ability to react to things realistically.

6. Don’t ignore the story for the joke

Story is EVERYTHING. Sure, your jokes could be funny… But if your story is weak, odds are, your audience won’t be returning to the theater or stolen Netflix account to re-watch. Make sure you plot out the arch of your story/sketch and be sure that jokes don’t distract too much from your plotline.

Sure, following a treasure map to an island full of sexy aliens might sound like a fun idea, but it might take away valuable page time from the rom-com you’re trying to write about a high schooler who fell in love with her math tutor.

7. Make it SHORTER

Shakespeare, an obscure playwright from the 1400’s or something, wrote “Brevity is the soul of wit.” Despite all of his other stupid ideas like “The course of true love never did run smooth” and his blatant rip off of Smash Mouth’s All Star “All that glitters is not gold”, he was actually on to something with this Hamlet quote.

Think about all of the times someone has told you a “funny story” that happened to them. Around the 30 second mark, you’re still fully invested in the story, maybe asking questions like “And then what happened?” After about 1 minute, you’re starting to wonder if the story actually is funny or if this friend of yours just wanted to hear themselves talk. Once that story starts creeping into the 2 minute range, you’re checking your phone and praying that someone else will accidentally spill a drink on you at this party just so you can get away from this loquacious nightmare.

I’ve included a shot of two different takes on the same scene. Can you tell which one is better? Which one would get more laughs from an audience?

SCRIPT VERSION #1

SCRIPT VERSION #2

Which one did you like better? I bet you it was the first script. And do you know why? The second script is much too long-winded and the dialogue seems very inappropriate for the child characters. You can Rule #5, keep it real, BY making it shorter! Killing two comedy birds with one stone!

8. Steal ideas

Some of the best stand up comedians in the world got their start by practicing other stand up comedians’ sets in the mirrors. Though outright joke stealing is incredibly frowned upon in the comedy community, stealing joke formats is certainly not. Do you have a favorite movie? What TV show makes you laugh the hardest? Go back and re-watch whatever it is. Look for joke types, structures, and scenarios and then rework those ideas to fit into your script.

If your favorite comedy of all time uses a lot of callbacks, use a lot of callbacks! If your favorite movie is about mistaken identities, mistake some identities! There’s no need for everything you write to be the most incredibly original thing in the world! Just KEEP writing! Actually… that’s good advice…

9. Keep writing!

Seriously, the best way to write a funny screenplay is to write 50 horribly unfunny screenplays. It’s important to stretch that writing muscle a bit before you sit down to write your masterpiece. Also, don’t become distressed if an idea you had just isn’t working out on paper. If it’s been a few weeks/months and it’s still not working, scrap it! You will have other ideas. Not every idea needs to go the distance. Comedy scripts are like ex-boyfriends. They suck up all of your time, they break your heart, and yet, you can’t stop thinking about them even when you’re working on your new script. Just don’t yell out the name of your old script at the typewriter!

10. Ask for help, you hopeless loner!

Comedy writers have the tendency to hole up inside of whatever dorm room, linen closet, or apocalypse bunker they’ve deemed their “writing space” and not come out for weeks at a time. This is a problem, considering your ultimate goal is to make other people laugh. Have other people read your screenplay! See at which lines they laugh at, which lines you were EXPECTING them to laugh at, and which lines they really DON’T laugh at. This is incredibly helpful information for you when you go to make edits. The more eyes, the better! Also, let’s be honest, you could use some more friends. Just be sure not to shove your script in someone’s face and say “Read it!” Always be sure the person who is reading your script has some level of emotional investment in you and actually cares if the script is good. And be sure to ask people other than your best friend Dan. Because you and Dan have the exact same sense of humor. Unless Dan is the only person you’re trying to impress. Then enjoy the script, Dan!

Works Cited

Bent, Mike. The Everything Guide to Comedy Writing: from Stand-up to Sketch, All You Need to Succeed in the World of Comedy. Adams Media, 2009.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: the Foundations of Screenwriting. Delta Trade Paperbacks, 2005.

Helitzer, Mel, and Mark Shatz. Comedy Writing: Secrets: the Best-Selling Book on How to Think Funny, Write Funny, Act Funny, and Get Paid for It. Writer’s Digest Books, 2005.

Smith, Carsen. “GOLD.” GOLD Comedy, http://www.goldcomedy.com/.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. M. Wiese Productions, 2005.

Ethnographic Films

History of Ethnographic Film:

Ethnographic film is a form of documentary film that explores people within a particular exotic culture or area of the world. Many argue that anthropology is demonstrated through visual symbols, such as clothing, facial expressions, rituals, etc., and therefore film and photography is the best way to communicate anthropological insights. Ethnographic film is therefore a subset of documentary film that attempts to blend anthropology with nonfiction film (Ruby XI). It is important to distinguish between a documentary about anthropological subjects and film created by anthropologists with the intention of studying and transmitting anthropological understanding. Scholar Jay Ruby argues that a truly ethnographic film is one that communicates these insights and serves as a teaching tool for anthropological studies.

But where does this genre find its roots? Documentary first became intertwined with travel when the Lumière brothers created the first portable camera (Mechaum). With this newfound ability to document on the move, the Lumiere brothers began travelling the world and capturing their experiences, taking on the name “expedition films,” or ‘travelogues. ” The first films followed the tradition of vaudeville shows, carnivals, and exhibitions and were seen as an objective account of a foreign culture. Because of this, they received little analysis from film studies because they were expected to give an objective view of reality, and therefore should leave no room for theoretical discussion. Some of the earliest travelogues were “A Gondola Scene in Venice,” “The Fish Market at Marseilles, France,” and “The Bath of Minerva at Milan, Italy” (Barnouw 13).

On of the most famous ethnographic documentaries (though it was not recognized as this at the time) is Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1928). The film attempts to capture everyday Soviet Russia through the lense of Marxist ways. Vertov’s goal with Man With a Movie Camera was to distinguish film as a medium that could inform, not just entertain. The film emphasizes the working class with the hopes of empowering society to work together. He wanted to communicate Marxist theories to the masses, hoping that audiences would see documentary as a social and political communication tool. Vertov was ahead of his time for this genre, but he set the groundwork for the use of cinema as a communicative medium of anthropological ideas. (Ruby 4)

Man With a Movie Camera received little praise when it was first released, however. ntil the 1970’s, ethnographic films lacked substantial analysis and the genre therefore never developed a structured way of theorizing films. The 1970’s, however, brought out the discussion of whether or not these ethnographic films should be seen separate from artistic works. Some began to recognize that these lines could be blurred, and many ethnographic documentaries had a specific film aesthetic that should be analyzed. Many also began to question how accurate these depictions really were, and whether or not they actually did a culture justice (Ruby 4). By the mid-1980’s many were up in arms about “the crisis of representation” in ethnographic films (Ruby 5).

Though early films were seen as an objective observation of a culture, it is widely understood today that cultural reality has multiple dimensions and it is difficult to grasp a full understanding of a culture through a two dimensional framed image. Visual anthropology is still seen, however, as an important tool in anthropological studies and analysis. Jay Ruby argues that visual anthropologies borrow stylistic techniques from all kinds of genres and have a wide variety of budgets and intended audiences. He points out that ethnographic films are rarely actually made my anthropologists, but rather they are made by amateurs with little knowledge about filmmaking or anthropology. Because of this, he argues that these films should be seen as a nonfiction film about an exotic people, rather than an anthropological work used for in depth cultural analysis. They are intended to supplement other methods of analysis and communication and therefore can not stand on their own (Ruby 1). The most successful ethnographic films, however, come from the anthopologists themselves, though there are very few of these films out there.

Ruby explains that his goal for ethnographic cinema is for the genre to achieve the idealistic fantasy in which films are not documentaries about anthropological subjects, but rather anthropological films created by anthropologists. He points to Tim Asch as a filmmaker who has come close to achieving this goal in his film The Ax Fight. Ruby argues that Asch is not concerned about theoretical issues, but rather he is concerned with collaborating with anthropologists to create a film that delivers anthropological insights. His films were created as a anthropological teaching tool for universities.

What are the ways in which ethnographic film can be problematic?

While documentary filmmaking can be an incredible way to spread knowledges and images of a certain culture, the genre can also become problematic when a culture or an area of the world is being represented by an outside. Ethnographic documentarians often attempt to create an objective yet personal representation of a place of the world, giving outsiders insight into what it is like to live in that world. Many forget to realize, however, that an image is never an exact duplication of reality, but rather a reflection of one perspective of reality. BIll Nichols calls this the “exhibitionist impulse” (Nichols) that has linked documentary film and travel, but many see this as degrading because it is seen more as sensationalism versus documentary film.

With ethnographic documentary becoming increasingly popular and images of foreign places circulating through media, these images of foreign places start to become a substitute for actual travel. One can feel as if they have been to a place after watching a feature length planet earth film, or feel as though they fully understand Buddhism after watching a feature length film about India. These reflections of perspectives of realities become a replacement of reality, and travel documentaries, in many instances, have taken the voice away from the people in these places.

Looking Ahead to the Future: How to make ethical ethnographic films

While there is no one answer to this loaded question, many scholars have looked at ways to provide steps to reflecting a more accurate representation of a culture without exploiting its subjects. David McDougall, one of the most widely known ethnographic filmmaker, has travelled all around the world to make films about the people of various cultures. In a OzDox Forum interview (around 9:45) , David McDougall discusses the ways in which the absolute truth can or can not be depicted through a documentary film. When asked, “What is documentary?,” McDougall does not attempt to give one solidified answer, but instead offers up ways to evaluate how accurate your representation of a person, culture, or scenario is.

Jay Ruby writes, “ One need only to consider that it is a human being with a socially constructed reality and point of view peering through the eyepiece of a device that further alters the recorded image as a consequence of the placement of the camera, the type of lens used, and so on, to realize how deficient film and realism has become….Filmic codes and conventions must be developed to frame or contextualize the apparent realizm of the cinema and cause audiences to understand the images as anthropological articulations” (Ruby 277).

Conclusion on Ethnographic Film

Ethnographic films are most successful when they serve as a teaching device about a culture, but they are viewed with the understanding that a film is a snapshot of a culture, rather than a pure reflection of an entire reality. In this sense, much of the responsibility comes from the audience members; it is their responsibility to remain aware that the screen is a one dimensional representation. Much of the problem comes from the audiences assumptions that an ethnographic documentary is the absolute truth of a kind of people. With this understanding, ethnographic films can steer away from over-representing a group of people and taking away their voice.

My Experiences & Advice to Students Who Wish to Travel

In the fall of 2016, I had the opportunity to travel around southern Africa (South Africa, Namibia, and Lesotho) while studying at the University of Cape Town. This part of the world is filled with some of the most diverse groups of people I’ve ever been around. The economic gap from one street to the next was mind boggling, while the variety of ethnicities and religions was extremely interesting to me. I wanted to capture it all to remember it for myself and to make movies out of it, but I often found myself stressed about how to do this without exploiting the people before me. How was I supposed to document these people without being the obnoxious American girl with a camera in everyone’s face? I was nervous, too, because I was one of the only Cinema & Media Arts majors to do a semester abroad.

The best piece of advice I ever received was from filmmaker Kirsten Johnson, who told me to use the camera as your diary. Though at first I wanted to get an objective documentation of the people around me, I soon realized that the reality was that that was not always possible. It’s impossible to be objective, because my presence did in fact affect the way people acted around me. Ms. Johnson explained to me, however, that it’s okay to document things that are affected by your presence, as long as you acknowledge that. I think this is a very important piece of ethnographic documentary that helped put me at ease about travelling around with my camera.

With that piece of advice, I made the camera my travel companion and my diary. Though I would not consider the films I made to be considered ethnographic documentaries necessarily, I’d consider them to be an autobiographical account of my experiences travelling, I think that the concerns surrounding both genres overlap a lot. Though this sounds minor, one aspect that helped put me at ease was the subtlety of the equipment I was using. I used a small Nikon CoolPix compact camera that could basically fit in my sweatshirt pocket if I wanted it to. With a small and subtle camera, I was able to blend into the crowd and film the people and the places, while my presences didn’t have to extremely alter their personalities.

Here are some of my works from my time in Africa:

SOURCES

Barnouw, Erik. “Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film.” Oxford University Press, 1993.

Mecham, Merritt. “The Documentary as a Tourist: Travel and Representation in Documentary.” Aperture, 2015.

Nichols, Bill. “Introduction to Documentary.” Indiana Press University, 2001.

Ruby, Jay. “Picturing Culture: Explorations of Film & Anthropology.” The University of Chicago Press, 2000.

DOGME 95

What is Dogme 95?

In 1995, while filmmaking celebrated its centennial, Danish filmmakers Thomas Vinterberg and Lars Von Trier penned a manifesto that birthed the Dogme 95 filmmaking movement. For a discussion of Dogme, the manifesto is a good place to begin.

Here it is.

THE VOW OF CHASTITY

I swear to submit to the following set of rules drawn up and confirmed by DOGMA 95:

- Shooting must be done on location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found).

- The sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa. (Music must not be used unless it occurs where the scene is being shot.)

- The camera must be hand-held. Any movement or immobility attainable in the hand is permitted.

- The film must be in color. Special lighting is not acceptable. (If there is too little light for exposure the scene must be cut or a single lamp be attached to the camera.)

- Optical work and filters are forbidden.

- The film must not contain superficial action. (Murders, weapons, etc. must not occur.)

- Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden. (That is to say that the film takes place here and now.)

- Genre movies are not acceptable.

- The film format must be Academy 35 mm.

- The director must not be credited.

Furthermore I swear as a director to refrain from personal taste! I am no longer an artist. I swear to refrain from creating a “work”, as I regard the instant as more important than the whole. My supreme goal is to force the truth out of my characters and settings. I swear to do so by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.

Thus I make my VOW OF CHASTITY.

Copenhagen, Monday 13 March 1995

On behalf of DOGMA 95

Lars von Trier Thomas Vinterberg (signed)

Why did von Trier and Vinterberg make this manifesto?

This is a very fair question. A list of ten rules seems, on the surface, like a sophomoric idea. So where did the idea of a Dogme 95 Manifesto and the vows of chastity come from?

NEW TECHNOLOGIES:

By the mid-90s, many people involved in filmmaking could see that digital technologies were improving and becoming poised to challenge the role of film. German filmmaker Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas) likened the emerging digital landscape to the development of sound cinema. He believed it would shake up the process of filmmaking, calling for an embrace of the new tools and a re-envisioning of the traditional filmmaking practices that went along with them. While this wasn’t a call for an organized, Dogme-like movement, Wenders did suggest European filmmakers were poised to develop the digital practices. He deemed the old ways of Hollywood filmmaking to be played-out. It was time for change.

The rules are somewhat shaped around an embrace of digital technology (the one about Academy 35mm film format was a rule for distribution, not for production). Almost all Dogme films were shot on video, because camcorders were easy to hold in a hand. A director could shoot a film with their own hands (Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration had him physically operating the camera in about 80% of the final cut). Digital meant footage wasn’t precious. Improvisation was encouraged, and resulted in more naturalistic performances. Locations looked real. Because they were real. Crews could show up with small, mobile, digital equipment, and shoot in a house or a restaurant, and it was much easier than doing things on a soundstage.

The most important and exciting part of the development of new, digital technology was that it was remarkably cheap in comparison to traditional film equipment. This was the first chapter in the democratization of media production. For the first time, a filmmaker didn’t need a backer with a ton of money. They didn’t need a beret, either. If they wanted to shoot, there was easier access to shooting. The Dogme collective saw it as an opportunity to scrub pretense, individualism, and excess away from the craft of filmmaking.

“I am no longer an artist”- pretentious in its effort to evade pretention

HOLLYWOOD AND GLOBALISATION:

The Dogme 95 Manifesto has a strikingly anarchistic tone to it. While this could be written off as a manifestation of von Trier’s flare for drama, or as a marketing scheme (we’ll discuss this later), there is also purpose and significance to the fact that this movement originated from, was managed by, and for the most part was mastered by Danish filmmakers. Denmark is a small country. It’s not a major player in the global marketplace. It imports a lot of films. Its own films are usually funded by The Danish Film Institute (a division of government).

In other words, Denmark was filled with small filmmakers. The kind who had chips on their shoulders, and were reacting against a Hollywood and American influence.

How does this make them different from other small, European nations though? It probably doesn’t. One thing that did make them different was that Denmark had Lars von Trier to help champion the movement. By 1995, he’d already made 5 films and they’d all gone to Cannes. He was still a relatively young filmmaker, who carried international prestige.

And he actually seemed to be bored with traditional rules and stipulations for filmmaking. Frustrated by the process of making his 6th feature, Breaking the Waves (released 1996, not Dogme), he teamed up with Vinterberg (a very young Dane, fresh out of the Danish Film School) to write the Dogme 95 manifesto as a way of reigniting creative energies and advancing the medium of film. He and Vinterberg saw the French New Wave and Italian Neorealist movements as good starts, which eventually became burgeious movements for the elite. They wanted to democratize filmmaking. In announcing the movement to an audience at the Odeon Theatre, Von Trier pelted a crowd with red pamphlets that contained the Dogme 95 manifesto.

This is beginning to sound like it is just a gimmick or marketing scheme…

So Lars Von Trier is theatrical. That much is true. And there’s not a clear way to prove that there weren’t marketing intentions behind the inception of Dogme 95. It’s also undeniable that the movement did receive a lot of press. I would like to argue that neither of these things really matters. One of the most common critiques against the Dogme 95 movement is that it doesn’t make sense to limit artistic capabilities in order to advance a medium. As evidenced by other modern and postmodern art movements, this is a somewhat unfounded stance to take. In literature, great advances were made with the 20th century’s embrace of literary minimalism. Kevin Brockmeier once wrote an entire novel in which every sentence contained 10 words. Jackson Pollock and The Sex Pistols didn’t err on the side of more artistic excess either. They reacted against tradition and challenged their medium’s form.

Thus, I find it unfair to say that putting stipulations on filmmaking inherently reduces the quality of film that could be produced. More so, with Dogme 95, the artistic merit can be found in the product.

Enough talk! Show me the films already!

I’m glad you asked. Dogme films were numbered as they were approved, so let’s begin with Dogme #1, The Celebration. Because Denmark was hesitant to finance Dogme films, it wasn’t completed until 1998.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xe3AySphzgI

Then here’s a trailer from Dogme #2, The Idiots.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sWaPAQwDS5s